Orangeburg Massacre: "Complete lack of respect for human life,' Cecil Williams says

By: BRADLEY HARRIS

Feb 06, 2018

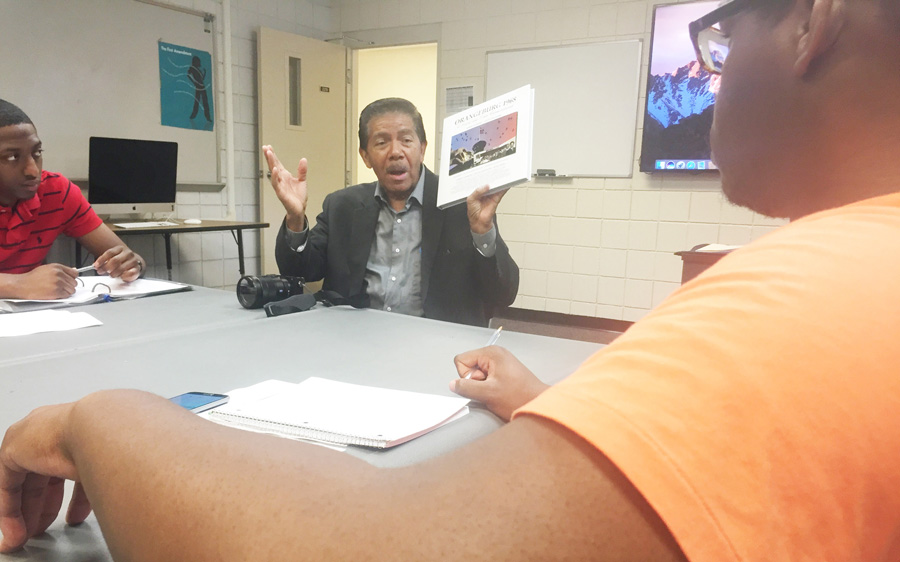

Photographer Cecil Williams speaks to Claflin multimedia students about the Orangeburg Massacre. He holds one of his four books, “Orangeburrg 1968: A Place And Time Remembered.” (Panther photo)

Photographer Cecil Williams speaks to Claflin multimedia students about the Orangeburg Massacre. He holds one of his four books, “Orangeburrg 1968: A Place And Time Remembered.” (Panther photo)

Fifty years later, the Orangeburg Massacre is still fresh on Cecil Williams’ mind.

The renowned civil rights photographer reflected on his role in the 1968 incident and the events that led to that horrendous night.

Williams, who was a recent graduate of Claflin at the time, was employed by both Claflin and South Carolina State College as a photographer.

Williams said key events leading up to the Feb. 8 massacre started days before.

Speaking to Claflin multimedia reporting students, Williams said the year leading up to 1968 was relatively mild as far as race relations in Orangeburg. This was due in large part to the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

But pockets of racism still existed in Orangeburg, Williams said. One of those places was the All-Star Bowling Alley in downtown, which still sported a “White Only” sign.

“That was a pocket of resistance,” Williams said. “That was one place that did not want to allow African-Americans to bowl.”

“Bowling itself did not bother me because I did not bowl, but still we wanted to feel that we lived in an atmosphere of equality, freedom and justice at that particular time in history, since we had fought so many battles to overcome and achieve the victories of the civil rights movement,” Williams said.

On Feb. 6, 1968, students from Claflin, S.C. State and nearby Wilkinson High School gathered at the All-Star Bowling alley, Williams said. The students were there protesting the segregation of the business.

“A student accidentally leaned on a glass and the glass broke. We all started running for fear of police authority. As that glass was broken, immediately a knee-jerk reaction happened and you saw the police officers go towards

their guns and billy clubs,” Williams said.

“I had a camera around my neck, and I started running too,” Williams said. “When a young lady fell down on the sidewalk, the city police, and I saw them with my own eyes, and I will always remember the image of them just taking a club and just beating the young lady right on the sidewalk where you come out of the bowling alley to Russell Street.

“They were just clubbing her and I think she required stitches to her head.”

Williams said students began to protest the police brutality by throwing rocks at windows of businesses and cars as they ran back to the campuses.

The following day, students were banned from assembling downtown and near the bowling alley, Williams said, and as a result, the demonstrations and events from that point on took place on the S.C. State campus.

“On Feb. 8, 1968, there were perhaps 250 students on State’s campus and they built a bonfire,” Williams said.

Williams said the students were demonstrating at the edge of State’s campus. The fire attracted the attention of law enforcement, causing them to be present at the demonstration.

“To keep them from going downtown Orangeburg, the governor and law enforcement officials and SLED had cordoned off the way for students to go downtown,” Williams said.

Law enforcement was positioned along Highway 601, which runs right in front of Claflin and State.

The events leading to violence began that night, Williams said.

“At about 10 p.m. highway patrolmen were instructed to load their shotguns,” Williams said. “They started approaching the campus.”

And though accounts differ on exactly why the shooting began, Williams said there is no disputing a fatal fact: “For nine seconds they pumped as fast as they could shoot. They just began shooting the students.”

Students first thought the gunshots were firecrackers because they could not believe that in 1968 police authorities would actually fire on them, Williams said.

Most of the injuries from the gunshots were to students’ heels and backs, he said.

“This was a complete lack of respect for human life,” Williams said.

“They didn’t use tear gas, they didn’t use a lesser lethal type of bullet which would not have done as much damage.”

The aftermath of the shooting resulted in the death of three students, Samuel Hammond Jr. and Henry Smith, who were students at S.C. State, and Delano Middleton, a student at then-Wilkinson High. The injury total was high, officially at 28, but more than that were hurt, Williams said.

The morning after the shooting, Williams came back to the campus to view the aftermath of the demonstrations and shootings.

“Around 8 a.m. that next morning I went back on the campus, and I entered where the shooting took place,” Williams said.

Williams recounted that it was a very cold morning, and that a mist was lingering over the campus. He vividly remembers his sight of the area where the demonstration and shooting took place.

“It was very eerie,” Williams said. “It looked like a battlefield, it looked like Vietnam or something,” Williams said.

“As I walked upon the grassy part of where the shootings took place, I looked down and I saw the spent shotgun shells. I picked up six of them and put them in my pocket,” Williams said. Williams said that minutes after he picked up the shells, a maintenance truck began cleaning up the area.

Williams said the shells he kept ended up becoming evidence of what happened the night before.

“Those shotgun shells led to the identification of the highway patrolmen who had actually shot the students,” Williams said.

Williams said he was called to a trial in Florence to add his testimony of the massacre. The jury found none of the patrolman guilty of shooting the students.

“The general impression that many in the news media were trying to paint and the police authorities’ version of it was that this was a riot and the students were fighting back and this was a very ignoble act of defiance against segregation, but it was nothing like that,” Williams said.

“This was a group of students who were trying to really achieve a victory and bring down this barrier that stood in front of them.”

Cecil Williams, Claflin University’s official photographer, is the author of four books about the civil rights era and the role Orangeburg and South Carolina played in major change. The books contain extensive photography and information related to the Orangeburg Massacre.